With the global discussion on artificial intelligence and machine learning becoming more robust with each bleak headline on the topic, public perception of the technology is marked more by skepticism and fear of the unknown than by evangelism.

Not for Babusi Nyoni. In fact, it’s conversations such as these that fuel the Zimbabwean innovator to reimagine the technology in ways that would fit a different context, particularly an African context. That’s why he’s experimenting with what he calls “ratchet AI.”

This Amsterdam-based developer has big ambitions - and that’s only his side hustle which has somehow not interrupted his love of travelling.

He started out as a graphic designer in his home country, before later settling in Cape Town to work in advertising. Nyoni grew frustrated with seeing his designs misinterpreted in the development stage, so set out to teach himself to code.

Soon he had mastered development languages php, Javascript and Python.

His enterprising spirit eventually led to him heading up digital creative at a large agency where he developed a custom AI for the beer brand, Heineken. That would be the world’s first AI football commentator, specifically created for 2016’s UEFA Champions League. While it was a world first, Nyoni seems more pleased by the offshoot application of the same tech.

He’d go on to use the same algorithm to predict forced migration patterns in Africa. Just for fun. It caught the attention of the Innovation services at the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), where Nyoni is currently engaged as a consultant supporting UX and artificial intelligence projects remotely. The team works with similar technology on a project that assists with predicting the movements of displaced people in Somalia.

A chat via video call, soon revealed that Nyoni takes his fun very seriously.

Take his AI-powered gqom robot, for example. Gqom, of which he is a big fan, is a South African music genre characterised by raw, unprocessed sounds and heavy bass. Nyoni was interested in this juxtaposition between cutting edge technology in AI and the DIY genre that originated in Durban.

“So why I chose that gqom and AI pairing was because I realised that gqom as a genre is very under-processed and raw-sounding. AI on the other hand, when it comes to making music currently, doesn’t make good music. It makes music that sounds as if it was put together by a robot. So because of these two things, I decided to pair the two because gqom that’s made by a robot is good gqom, because it’s bad gqom, right?” explains Nyoni.

Though it was a frivolous experiment, the gqom robot made him realise that there was a need for AI to be given some kind of grassroots context.

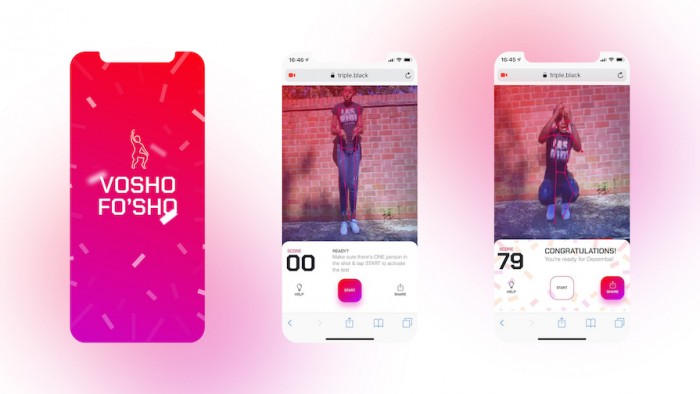

Still working within the gqom space, he then created the Vosho app. Vosho is one the dance moves associated with the genre, which involves contorting the body to move up and down along with the bass of the music. The app would rate your vosho based on pre-selected criteria.

“The way it works is it paramaterises the points of your body and then when you tap the button to rate the dance move, it looks at how quickly you go down, how far you went down, how tall you are, and then how quickly you come back up. How quickly you get up is also a big component of vosho, because it kills your knees and your thighs. So it gives you a score based on these parameters,” he says.

Nyoni deliberately made the app available via web and mobile browsers (as opposed to a standalone app), as he was skeptical about creating barriers to entry. The results showed that it was accessed by more than 300 devices, most of which were really low-end. A nod to his acknowledgement of context, given the prevalence of lower-end feature phones across African countries.

“You have people with super low-end devices trying to access what is literally the cutting edge of technology right now, and they don’t know it, because nothing’s telling them that this is some crazy advanced tech, it’s just, they have the context for it and they’re like ‘cool, I wanna try it out’.”

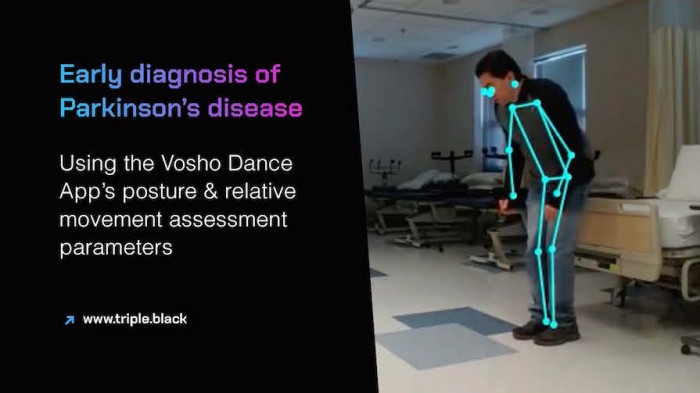

Gqom and vosho are niche apps, but nevertheless the vosho app was relatively successful. Successful enough to convince Nyoni that the same algorithm could be used in another, more serious application. With parameters in place to track body movements and with the ability to track these over time, he started experimenting with how this could work as a tool to help with the early diagnosis of Parkinsons disease.

He worked with a medical professional to set the parameters that would help an individual determine that it was time to consult a doctor, particularly in cases where regular access to a healthcare facility was not the norm.

In the same way that you would have your friend rate your vosho for you, you would have a primary caregiver or someone near you understand what it meant over time for you to walk in a certain way and what that might indicate. This early diagnosis, or description, could then be used by a medical professional to get a proper understanding of what is happening with a patient.

It’s easy to see now from where Nyoni derived his optimism about artificial intelligence.

He agrees that the industry almost developed too fast for its own good, resulting in companies not really knowing what they wanted to do with the tech. He’s confident that he doesn’t fall into this category.

“The variant of AI that I interact with is one that is not defined by anyone else but myself. I know what I want the tech to do, so it’s not like I’ve inherited an algorithm that does this, this and that.” he says.

“I have this theory that no one knows what they’re doing in artificial intelligence, and for me to be able to manouevre in that space and move more quickly than people who have PhDs and whatnot and actually do meaningful things with the tech, means that there’s a gap between what is being made and what can be made with it.”

Nyoni knows exactly what he’s doing and his vision is clear. That clarity of vision is perhaps derived from the understanding of what needs to happen in an African context to make a first of artificial intelligence on the continent. Key to that vision is equipping Africans with the knowledge and skills to imagine the tech on their own terms, holistically, rather than simply equipping them with one of the skills within the production line of someone else’s tech ecosystem.

He says that the young African workforce is being trained to code and develop and he uses the analogy of car manufacturing when workers are told how to “put the light on a car,” as opposed to thinking around what the cars of the future could look like.

“What is being taught is how to then deal with what the rest of the world has come up with and then just have the least impactful contribution, but of course the one that is most people intensive,” he explains.

Nyoni’s commitment to African-focused projects extended further into the murky waters of the ethics of AI. Since there is no global ethics policing for self-driving cars (yet), he built one that uses Ubuntu as a value system. Ubuntu is an African concept and philosophy that encompasses human virtues, compassion and humanity.

It came about in 2017 when one of the biggest tech sites released survey results which indicated that the majority of the community felt developers themselves should be responsible for AI ethics and algorithms. But when more than 80% of those respondents were white males, it becomes problematic. This narrow demographic means that there isn’t a diversity of experiences and perspectives to draw from, and which will inform an inclusive ethics code.

“So you don’t have representation in the room, but you’re also saying that we should be the ones who control what happens, who dies, who lives, etc. This is why Africa needs to get in on the conversation as soon as possible,” says Nyoni.

He says the ethics library is a bit ahead of its time, because it’s built for a future in which there are multiple manufacturers of self-driving cars and autonomous software is more commonplace. But more than that it was about making his voice heard.

“This was more like a leap into the future, but one that was more based on showing that we can be heard in these kinds of spaces if necessary, and not just to wait until people need developers to roll out something,” he says.

Whether being heard means creating frivolous apps that rate your dance moves, or building a tool that will no doubt be relied on in the future, Nyoni’s work is carefully towing the line between homegrown relevance and cutting-edge innovation. His projects are made less for a market, and more to harness conversations around what’s possible as it relates to Africans.

“AI needs to become more and more 'ratchet' in order for it to become more and more approachable. I say 'ratchet', because I don’t just want it to be just accessible. It should be so accessible, it’s silly.

"There’s a need for AI to be made more accessible to a generation that doesn’t have the hang-ups we might have around who the people are who built AI tools. I definitely think the upcoming generation needs to understand that this is a field that they can totally own if they wanted to because no one actually owns it,” he says reassuringly.

Read more on AI:

Joy Buolamwini uses art and research to show the social implications of AI

How two researchers hacked software to create a functional AI for their diabetic son