From the Series

So much more than an architect, Bjarke Ingels put it well when he said at Design Indaba Conference 2012:

Architects should become designers of ecosystems, flow of seasons and resources.

During his presentation at Design Indaba in Cape Town on 1 March 2012, the Danish architect demonstrated how he is executing this philosophy when he revealed plans for a skyscraper that would transform the Vancouver skyline. Named Beach and Howe St. after its location on the corner of Howe and Beach, its complex urban conditions demand a solution that goes beyond the realm of building design.

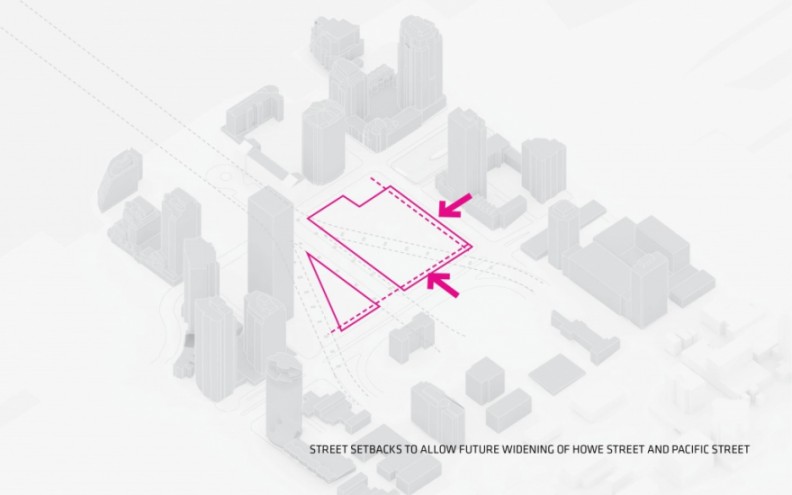

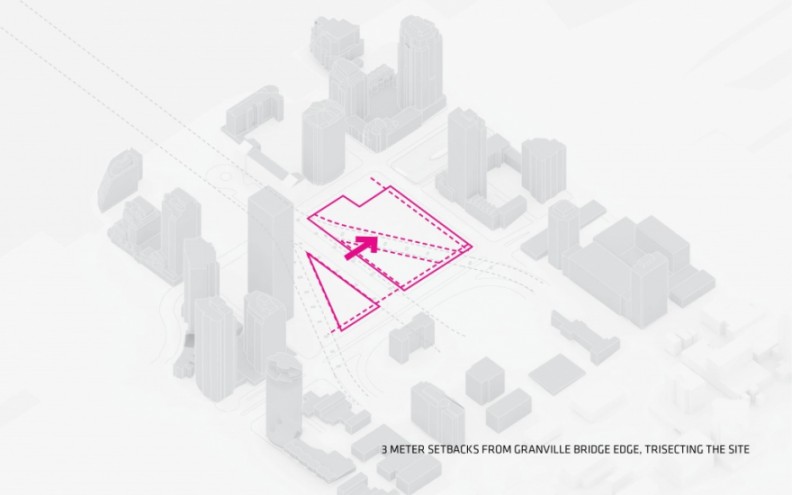

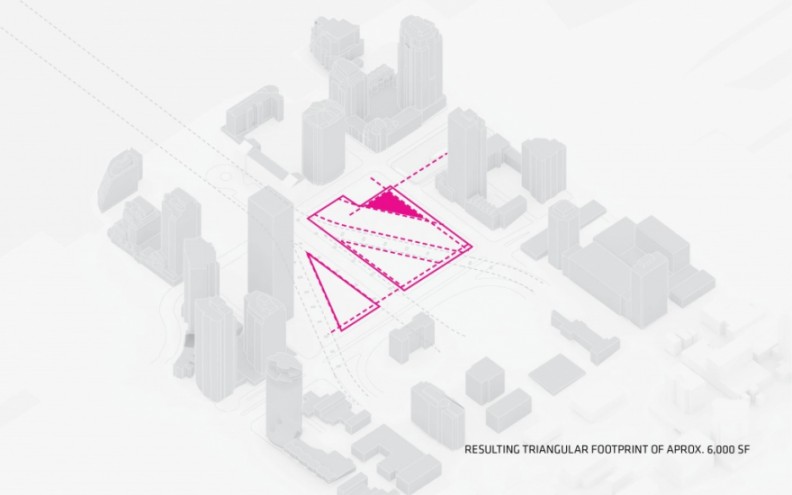

At the core of its brief lies the necessity to minimise the building's footprint on the groundlevel, so as to infringe on public space as little as possible, to optimise the desirable living space within the building, to circumvent the neighbouring buildings and Granville bridge, and to avoid blocking sunlight to an adjacent park.

As the founding partner of BIG describes:

The Beach and Howe tower is a contemporary descendant of the Flatiron Building in New York City – reclaiming the lost spaces for living as the tower escapes the noise and traffic at its base. In the tradition of Flatiron, Beach and Howe’s architecture is not the result of formal excess or architectural idiosyncrasies, but rather a child of its circumstances: the trisected site and the concerns for neighbouring buildings and park spaces.

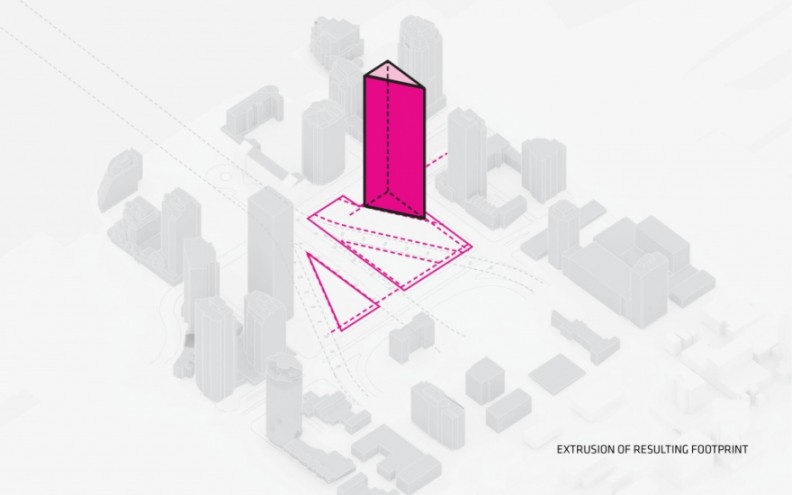

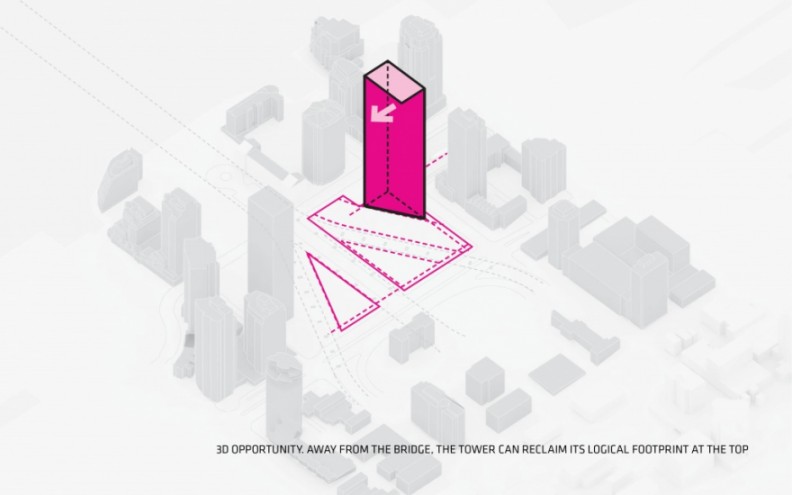

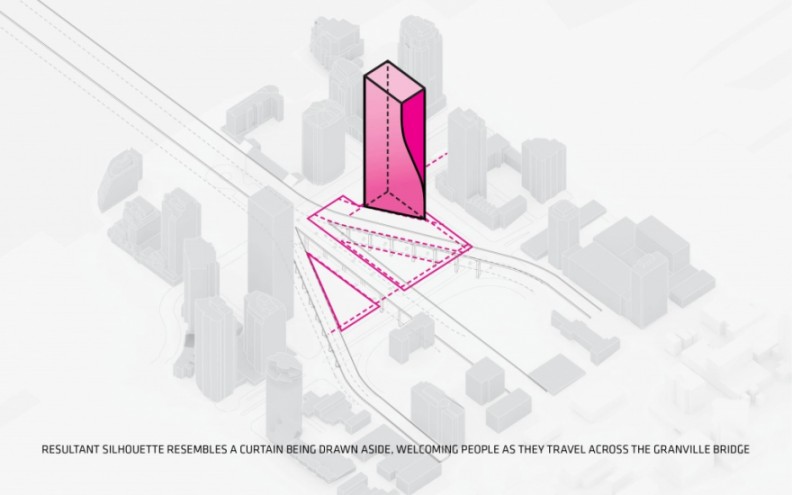

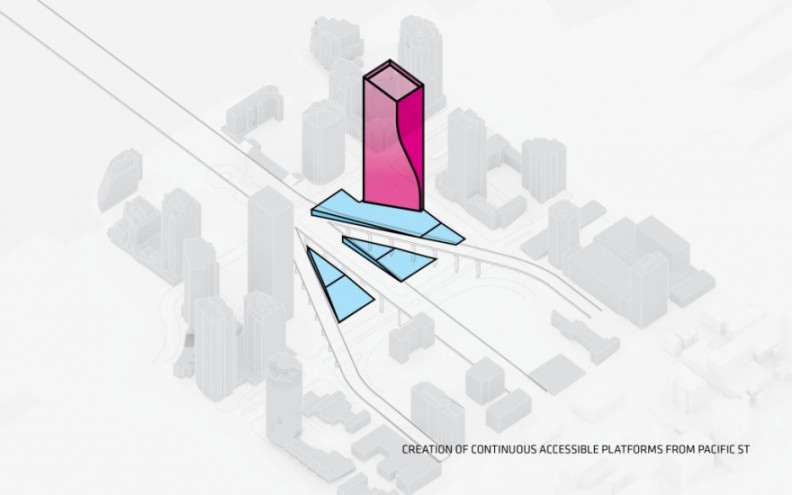

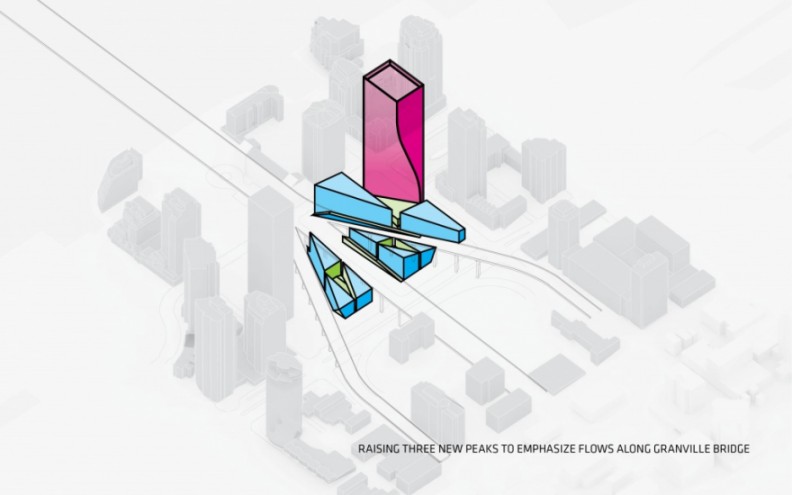

BIG's proposed design provides a solution to all of these criteria. Starting with a small, triangular base, the building twists upwards, veering away from the noisy, polluted vicinity of the Granville bridge and widening as it climbs towards the sky, to culminate in a spacious rectangular top floor. The bulk of the building's habitable space is thus prime real estate up in the sky, while it's less desirable lower levels are reduced in capacity, which simultaneously creates a newly opened space on the exterior under the Granville bridge that becomes a dynamic neighbourhood hub for public use. And the angles at which the building twists ensures that the park is not overshadowed but rather creates protective canopies over the street, creating a new form of weather-protected urban space.

As BIG explains:

As the tower ascends, it clears the noise, exhaust, and visual invasion of the Granville Bridge. BIG’s design reclaims the lost area as the tower clears the zone of influence of the bridge, gradually cantilevering over the site. This movement turns the inefficient triangle into an optimal rectangular floor plate, increasing the desirable spaces for living at its top, while freeing up a generous public space at its base. The resultant silhouette has a unique appearance that changes from every angle and resembles a curtain being drawn aside, welcoming people as they enter the city from the bridge.

If necessity is the mother of invention then great design is its brainchild, combining functionality with art in a mix that, in his case, Bjarke likes to call "architectural alchemy".

BIG was commissioned by Canada’s premier real estate developer Westbank, established in 1992, with over $10 billion of projects completed or under development, including the Shangri-La luxury hotels in Vancouver and Toronto. The 490-foot-tall Beach and Howe mixed-use tower by BIG + Westbank + Dialog + Cobalt + PFS + Buro Happold + Glotman Simpson and local architect James Cheng marks the entry point to downtown Vancouver, forming a welcoming gateway to the city, while adding another unique structure to the Vancouver skyline.