Part of the Project

For the last 9 weeks I’ve been living in the centre of Mexico City.

With a metropolitan population of about 21 million people, this is about 40% of South Africa’s population in one vast, continuous megatropolis. Almost 70km from North to South and 50km from East to West, it takes 3 hours to move across the City by car, on a major arterial, at off-peak time. Only then do faint traces of the open landscape start to emerge.

Continuity

Mexico has been a City for a very long time. The Spanish built the existing core directly on top of the Aztec City of México Tenochtitlán. The Zócalo, or main City Square, is in the heart of historic Centro, its position and size exactly the same as the original Aztec Plaza. Where the space was once contained on its four sides by monumental ceremonial pyramids, the Colonial Catedral now contains it on one side, and the Palacio Nacional – the office of the City Governor – on another.

The Aztec trading, ceremonial and social City was an island in the middle of a huge lake that the Spanish Conquistadores drained to reach and conquer their foe. The four primary roadways that connected across the lake into the Aztec Plaza remain as the main streets connecting into the Zócalo. This is continuity. a city of distinct neighbourhoods

I’m living in Condesa, one of a set of ‘villages’ that were once retreats far outside of the colonial city limits. Though retaining their strong individual identities when you’re in them, and by reputation, they’re now so close to the centre of the City, and so far from the perimeter, that it’s hard to believe they were once out in the countryside.

About 20% of the city population lives in the core that progressively densified and diversified from its origins until about the 1960’s. This is when the other 80% started arriving. The City did not expect or plan for this massive urban influx. There was no room inside, so the wave settled where the lake once was, and over about the same vast surface area, from the edge of the City core to the distant containing mountains and volcanoes. Self-built, almost entirely of raw grey concrete blocks, it’s what some architects here call the ‘Cuidad Tabicón’, the ‘concreteblock city’.

With the exception of Reforma and a ghastly newish Houston-like glass and concrete office and residential district called Santa Fe, the city is mostly between 2 and 6 stories high. It’s a remarkably human scale for such a vast, dense and diverse city.

Human scale and character

Adding to this sense of human scale, the City is also not laid out on a continuous orthogonal grid. Rather, it’s a web of diagonals, ellipses, and curved avenues resulting in an unusual number of buildings with acute corners, many designed in the Art Deco and Modernist periods of sleek boat shapes.

These unique and wonderful forms are striking counterpoints to a predominantly colonial Spanish language of orthogonal form and embellished detail. They are experienced as a constellation of unique landmarks whose identity is ‘era’ rather than ‘shape’.

Buildings in the core – almost all of them mixed in use – touch each other side-by-side to define streets, public squares and urban parks. These are the primary building blocks of the neighbourhoods – both physical and social.

Each of their distinct characters is informed by the layout and detail design of its street network, scale and public space typology. Some have small circular plazas with fountains and benches, trees and lighting, around which cars move at the intersection of their main streets and avenues. We would call them traffic circles, but their design, identity and use belongs to the pedestrian experience not the car.

Others are identified by having a park at their centre, circumscribed with elliptical avenues with 10m wide treed linear walking and cycling parkways between traffic lanes.

All these unique characteristics are key aids to navigation, especially for strangers to this almost infinite urban landscape.

Continous, vibrant, accessible commerce

On the edge of these neighbourhoods are others of a quite different kind, each dedicated to the trading of specialist products like plumbing and electrical goods, or timber supply. Here the streets are a continuous network of manically buzzing ‘marketplace’. If you need a length of copper pipe, you stop the car, order and pay over the street-side counter. If it won’t fit in your car, it’ll be delivered in a couple of hours.

Imagine our own hardware superstores many times multiplied in range and stock, spread throughout a neighbourhood. This is the reallife non-corporatised economy. Convenience mixed with wide product range, at low-cost, with specialist technical advice running through generations, enriched with incidental conversations on the street or at the counter.

Limited suburbia

Suburbia does exist. But because it is such a low proportion of the City fabric, it is experientially almost nonexistent. Pedregal, for instance, is a neighbourhood on the south of the City where there are single houses on single sites with fences, lawns, flower gardens and swimming pools.

It was conceived and designed by Luis Barragán, probably México’s most revered architect of the 20th Century, and a very successfully property developer. I haven’t seen inside the houses, but the book ‘Las Casas del Pedregal 1947-1968’ [The Houses of Pedregal] is a tour de force of Mexican modernist domestic architecture par excellence. It represents a moment when the moneyed intelligentsia, industrialists and business people invested in Mexican modernism as an ideology, an emblem of national identity, and a symbol of progress. The simplicity and rigour, use of natural materials like volcanic rock and timber that characterizes the period, still runs strong in the best of contemporary Mexican architecture today.

Living not housing

I am living in a 2 storey building off a pedestrian friendly, tree lined, busy street of 2 car lanes in each direction plus a Metro-Bus lane.

Within about 10 minutes walk from ‘home’ is a stationary store, supermarket, hole in the wall plumbing supplier, electrical supplier, park, book store, bank, church, shoe repair, laundrette, flower kiosk, patisserie, hair salon and spa, upholstery repair, bicycle repair, Metro-Bus station, underground train station restaurants, bars, countless cafés… the list goes on.

These are the direct benefits of density, diversity, and connectivity, glued together and given life by public space.

The 110 sqm, double storey apartment is one of 14 in what is called a Vecindad – a small compound where the houses are so close to each other that they form a community of neighbours. The Vecindad is a predominant housing typology across the city. They range from those renting rooms only, with communal cooking and ablution facilities, to those where the upper echelons of society live.

Where I am, there are 7 apartments on either side of a 5m wide and 50m long, shared ‘courtyard’, open to what feels like a relentlessly blue, still and warm winter sky. Like Durban in June, it’s hard to call this winter, although I believe the cold is still coming. The courtyard is accessed through a wrought iron gate between the street-side tables of a café that is part of the Vecindad but opens onto the sidewalk outside.

On the other side of the gate from the café is a small hair salon and spa next to which is a patisserie. As well as the gate, the café and client activity of these businesses are effective passive security measures, gatekeepers. This is useful in a city regarded as one of the most dangerous and violent on the planet. Although with all the people out and about on the streets until two in the morning, this statistic is hard to believe. In most parts of the core of the city, cars are relatively safely parked on streets overlooked by apartments, or are in inexpensive valet-serviced parking lots; in newer buildings, they’re in basement parking.

A network of vibrant opportunity

Mexico City does not supply pressurised water, nor is the supply regarded as drinkable. Across the whole city, it dribbles into cisterns under every house or building, including 30 storey office towers. From there it’s pumped to rooftop tanks that provide pressure to the internal water reticulation. Every day everyone deals with the fact that water is a scarce commodity in this arid climate.

On Wednesdays, 20 litres of bottled water is delivered on the shoulder of a man whose job it is to do this. He shouts his coded call from the street gate so you know he’s there and can let him in. On Friday’s the gas man arrives in the same way to check if he should carry in and up the stairs to the roof, on his shoulder, a 30 kg replacement bottle of gas. He is pleased if you offer him a glass of water. He is more pleased if it’s Tequila or Mezcal.

Across from me is a small publisher of immaculate hand type-set books of literature and poetry [tallerditoria.com.mx]. Their books are available across the country, including in the massive bookstore 15 minutes walk away. Two doors down the courtyard, another apartment is converted into the office of a national architecture magazine called Arquine [arquine.com]. Through mixing uses, diversity happens at very scale.

Within the first 2 weeks of being here I had had incidental conversations with all of these people as well as many of their friends and associates that arrived to visit them while I was sitting on a bench outside the door, piggybacking on the free-access Arquine internet connection. I’ve met an editor of poetry and literature from Uruguay, a Franco-Mexican filmmaker living in Sao Paulo, Brazil, a maker of fine timber furniture living in Oaxaca about 4 hours drive from Mexico City.

Quality of life

About 5 minutes walk away are Parque Espana and Parque México. Both are relatively small treed urban parks surrounded by roads overlooked by streets of apartments. They are ‘urban forests’ with a balance of walking paths, planting and public use activities.

This is where owners let their dogs off the leash to bound through the fountains, delighted with their freedom; where 5 year olds make friends for an afternoon, or for life; where parents make business connections and have unexpected conversations with each other while pushing their children on swings; where mothers have some down-time on the sophisticated outdoor exercise machines under the trees; where lovers get some intimacy on the benches; where weekend markets sell food and showcase local musicians and where you take an almost free-use bicycle to cruise around this part of the City and drop it off at another digitally managed street-side depot when you arrive at work, or visit an exhibition [ecobici.df.gob.mx].

Civic identity

Based on the Champs Èlysées in Paris, Reforma is one of a few civic avenues that arc through the City, connecting it together at the overall scale. Another is Insurgentes [Insurgents] and another Revolución. Toward the west, Reforma runs through Bosque de Chapultepec, the city’s main park. Here it is a grand boulevard with a linear treed parkway down its centre with modern sculptures at every 50 meters or so that seem to go on for miles.

Set within the park are some of the city’s major galleries and museums, like the Museo de Antropología e Historia [Museum of Anthropology and History]. Each of the major pre-Hispanic Mexican civilisations is represented in one of three separate buildings. Together with the entrance building, they define the edges of a large open-to-sky public plaza. At this end, an immense umbrella-shaped roof supported on a single column conceptually links the independent buildings, clearly representing the idea of ‘one México comprised of many heritages’.

This sense of ‘unity from diversity’, continuity, and constant transformation is everywhere.

This is a city

From gritty, dense and diverse neighbourhoods, rich in everyday social and cultural experience, to avenues of national identity, this is a city. This is what makes it possible for there to be a vibrant economy constructed of layer upon layer of accessible opportunity. From thousands of gas bottle carrying men at one end, through millions of small businesses in a wide and varied middle, to a few corporate executives at the other.

This is what makes explorative, pioneering and diverse design and cultural production possible. And for there to be vibrant city markets that supply an unimaginable diversity of food, in many cases almost directly from producer to consumer. Large supermarkets and hypermarkets are very few and far between.

This is what makes social life in public, semi-public and private spaces possible, where people incidentally and spontaneously interact with each other, where new and inspiring conversations happen that change lives. And where society continuously and dynamically evolves and reinvents itself.

This is a city, that self-generates economic, social and cultural exchange, creativity and productivity; grown from the fertile fields of difference and the unexpected, unified by one National Identity, and flourishing because of density, diversity, connectivity and public space.

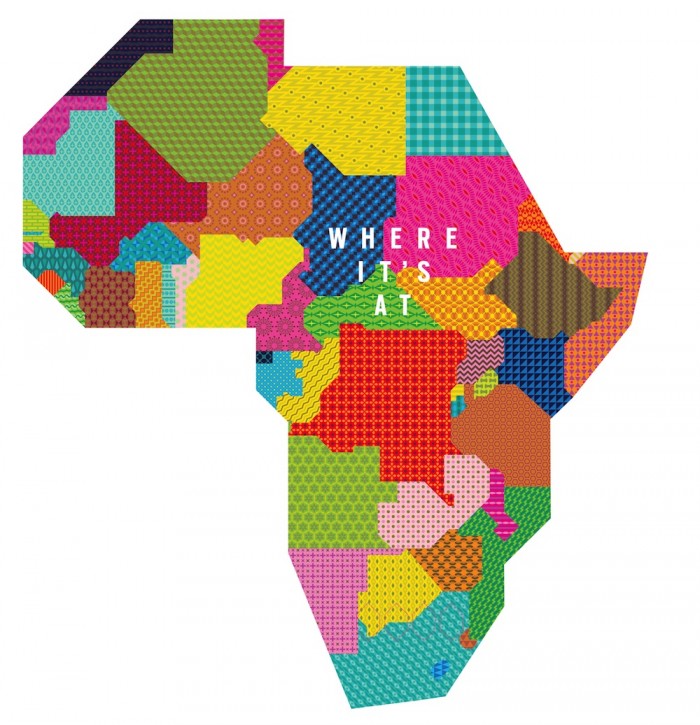

This article was originally commissioned for Where It's At, a Design Indaba publication created in collaboration with Richard Hart and disturbance design published in 2012.