There is a pair of images of Buhlebezwe Siwani taken on an undisclosed beach. One sees the visual artist standing in the waters, the waves of the ocean rolling wildly toward her. The second photograph captures her submerged in the waters save for her head, billowing clouds and sea spray visible above her. Part of her 2015 photographic project, uThengisa unokrwece elunxwemene (which translates to She Sells Seashells by the Seashore) this wouldn’t be the last time Siwani’s artistic practise would draw her to natural bodies of water.

In 2017, Siwani revisited this space as a site for her visual art, producing two more self-focussed photographic series, iGagasi and ILanga litshonile.

“I think that was my first diptych during my Masters’ programme,” Siwani tells me of the earlier work. “It speaks to fear of the ocean and the kind of spirit that the water represents – what natural bodies of water represent in African spirituality. You know, a lot of people go to church by oceans, a lot of people do certain things as rituals or customs, you throw money into water – it’s not just a recreational space.”

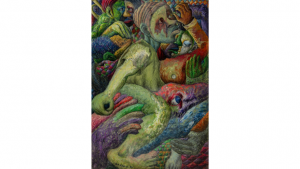

Similarly, Siwani’s vocation as an artist is far more than just something she does for fun; it’s her way of exploring herself, interrogating the world around her, and interpreting her experience of living as both a creative and a sangoma (traditional healer). Engaging with human journeys in all of their complexities, the Wits School of Arts and Michaelis-trained artist uses photography, performance, installation, sculpture, video and drawings to touch on these multiple facets of her consciousness – parts of herself she comfortably acknowledges as inextricable from one another.

“I think I’d always known,” Siwani, who recently showcased her work at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair, explains to me of her journey to heeding her ancestral calling of ubungoma – the ancient African healing tradition. “It’s definitely influenced my work. I mean, my work is about journeys and the understanding and liminal characterisation of the self. I don’t see myself making work about anything other than it for the time being because it’s so intrinsic in the way we see ourselves as Africans, you know?”

Though she admits to having become disillusioned with the art world for a short while back in 2011 – “It tends to do that. Everything just kind of pissed me off” – the creative process has long been an embedded part of her life, something she was naturally drawn to early on. “There was a place called Fuba in Newtown,” Siwani recalls, “you could leave your kids there – they offered music, dance, art and drama.” Her mom, a journalist, would leave her daughter there during the week, where she was mentored by professional visual artists. While her mother had signed her up for dance lessons, the young Siwani decided to go and draw.

“It was simply another foray into the same things that I got encouraged to do at home – not necessarily just drawing but the arts in general.” I ask if she was one of those rambunctious kids whose artistic inclinations led to informal artwork on her family home’s walls and Siwani laughs and says no. Due to her mother’s occupation, there was always an ample supply of paper. “If an article she was writing wasn’t working, she’d be like ‘Hey, here’s a piece of paper. Do whatever.’”

As an artist, one of the ways Siwani chooses to explore her experiences is through using her own body as a means of communication. She understands these experiences better than anyone else, she tells me, and were she to use another’s physicality – one with it’s own stories – she would need to be sure of what that story is. “This is why I put myself in. Who better understands my own experiences, my own memories and my own journey than myself?”

From her mesmerising live performance pieces and dazzling sculptural creations, to the inspired visual documentation of her art, Siwani’s body of work touches on difficult subjects without shying away from their complexity. Topics like race, colonisation, apartheid, gender, sex, language, and anthropology all emerge in her work, encouraging viewers to ask questions rather than simply providing them with answers.

Right now, Siwani is in the Netherlands where she is participating in a rather unusual artist recidency. Based in a mental institution in a little town called Den Dolder, she is required to work with the patients and create an art piece through her interaction with them. “I got invited because I’m interested in illness, you know – the liminal space between what drives you crazy as a sangoma – I guess that would be a thing – but also the historical links,” she explains.

Having lived a rather nomadic existence – she's lived in the Eastern Cape, Johannesburg and Cape Town – Siwani’s work continues to see her roaming the globe. Earlier this year, she exhibited her work alongside South African artists Grace Cross and Thania Petersen at LKB/G Gallery in Germany; was included in the Art/Africa, le nouvel atelier exhibition at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris and more recently had a solo exhibition at Galeria Madragoa in Lisbon, Portugal.

With all these stamps crammed into her passport, I ask her whether the concept of ‘place’ plays a strong part in the art she creates.

“It really, really does,” Siwani says, admitting to always getting nervous when leaving home. “South Africa is South Africa and different parts of South Africa, they’re different – they’re specific to particular years and particular histories. So, when I go to somewhere like the Netherlands, where I am right now, I’m just like, wow, we have such a deep history and such a deep connection with this particular country.”

It is these disparities and connections that Siwani continues to artistically explore, discovering unique parallels within each space she moves into. With each piece of imagery she creates, she feeds her audience particular social signs and symbols, leaving it up to them to decipher. “I’ve always said if art doesn’t engage socially what are you making it for? If it doesn’t engage with the social economics of our time, with the political economics of our time then why are you making it?”